By Paul Liam

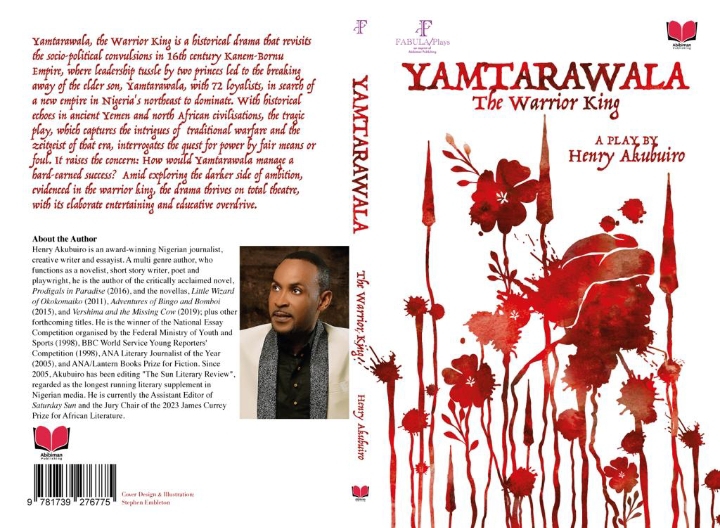

Yamtarawala a 2023 play published by Fabula/Plays an imprint of Abibiman Publishing, is a historical play encapsulating the nuances of palace politics in a traditional northern society in the context of the Kanem-Borno Empire in the 16th century. It traces the historical antecedents that often characterized the evolution of new empires in ancient societies which were driven by the fallout of major actors within a hitherto organised unitary power structure. It is a modern dramatization of the emergence of the Biu empire through the legend of its founder, the warrior prince who later became a king, Yamtarawala. As the Narrator of the play states, “This is the story of a great warrior, who was schemed out of the kingship of the Kanem-Borno Empire and the Ngazargamu palace as the first son. He didn’t stay behind to fight his detractors, but he took 72 men from Ngazargamu and headed for the Mandara Mountains to begin an empire-seeking adventure that lasted many years. He came across many tribulations, but he never cowered.” This passage summarizes the main plot of the play around which other events unfold. The playwright, Henry Akubuiro, employs a simple linear narrative technique that is accessible to all categories of audiences or readers.

The play instantly reminds the reader of other notable plays centered on kingship like Wole Soyinka’s Death and The King’s Horseman, Ahmed Yarima’s Attahiru, Yahaya Dangana’s The Royal Chamber, Wale Ogunyemi’s Queen Amina of Zazzau, Abdullahi Ismaila’s Emir Emeka and Isaac Attah Ogezi’s Embrace of a Leper, among others. While the rich history, cultures, and traditions of the peoples of southern Nigeria have been documented through literature and film, the north suffers from the dearth of literary representation of its phenomenal histories and cultures and even where such narratives exist today, they have not penetrated the consciousness of the mainstream audience, they remain regionalized. It is not surprising that it has taken Akubuiro, a southerner to bring to the fore of public discourse the enigmatic story of Yamtarawala of the Kanem-Borno Empire. It suffices to say that, the play, more than paying homage to an impactful history, offers readers a modern and refreshing anthropological perspective into a legendary story that most readers are encountering for the first time. It is a well-researched theatrical textualization of the coveted legend of the ancient people of Biu in present-day Borno State of North East Nigeria, and it shares some import with Muhammadu Bello’s Gandoki, in terms of its thematic preoccupation with the valor of resistance to British colonial invasion of precolonial northern Nigeria.

One of the unique features of Akubuiro’s thematization of the legend of Yamtarawala is its departure from the common trope of a protagonist fighting to exert vengeance against his enemies, especially in the context of royal politics and powerplay where an aggrieved prince struggles to reclaim his stolen birthright to become a king in a situation where the said king has been schemed out of his right to become king as a first son. Contrary to this well-known narrative trajectory, Yamtarawala, the prince who lost his right to ascend the throne of his father as the first son, demonstrates an uncommon sense of rationality and self-consciousness that questions the plausibility of such a representation given that the play is set in a period where people were driven by competitiveness and vindictiveness and the urge to prove their manliness through violence or any means available to them, especially for a man who boasted of killing lions as a teenager. The representation itself is not faulty, it highlights the unique character of Yamtarawala as a man with a vision bigger than the throne he was denied. Instead of fighting his younger brother to reclaim the throne, he chooses to walk away from Ngazargamu to find his empire to prove a point to his younger brother, Umar, and his detractors that he is truly bigger than the throne he has lost. Hence, Yamtarawala sets out with only a handful of soldiers to conquer other communities through wars to form his new kingdom.

Yamtarawala’s personality illustrates the interplay of power, valor, deceit, wit, and patience in achieving one’s target. He fought several wars and professed fake love to various princesses to gain access to their father’s or community’s protective charms which previously made it impossible for enemies to defeat them. However, beyond Yamtarawala’s empire-seeking exploits, the play also reflects on a significant aspect of the people’s history that is not given much attention in contemporary northern Nigerian literature; the Arabian slave trade and the divide between Islam and tradition. Although not portrayed in detail, occasional references to the subject in the play serve to remind the readers about that part of history that is often neglected in the discourse of the evolution of northern Nigeria. This is corroborated by the exchange between Kwatam Gambo, the Princess of Miringa, and her maid Pitum, and then in her exchanges with Yamtarawala in the forest where Yamtarawala and his men laid in ambush.

“There are slave raiders from Maiduguri looking for whom to catch and sell to Arabian slave merchants, and enemies are waiting to strike.” Kwatam Gambo says to Pitum. And reacting to Yamtarawala’s advances she further enthuses, “Something about your face tells me you are telling the truth, though you look like an Arabian slave hunter or one from the Kanembu area after Lake Chad.” P.57-58. Such a portrayal cannot be an accident but a deliberate attempt by the playwright to highlight this very important piece of history as a symbolic representation of the pervading slave raids and merchants that characterized the era in which the play is set. Similarly, Akubuiro highlights the importance of an oral knowledge acquisition and transfer system through which older folks tell stories to children in the community about their ancestry and cultures using fables or folklore. Consequently, the significance of storytelling in traditional African societies is illustrated through Yamtaralawa’s interaction with children before inviting his deputy Galadima who tells the children a story. Yamtarawala invokes the essence of storytelling an embodiment of the culture and values of a people, thus,

“Storytelling has been part of our culture right from time. We have left Ngazargamu, but we didn’t leave our cultural heritage. Wherever we go, we go along with our culture. Tonight, you are going to hear a new story.” P.43. The role of storytelling in perpetuating a culture of learning and awareness among children in traditional society is an unmistakable agenda of the playwright in highlighting the importance of learning about the rich cultural heritage of the past to strengthen the consciousness of the younger generation in their cultural identity. This assertion is further buttressed by the fact that the stories are being told to impressionable children in the text who are eager to learn about their heritage. To drive home this point, Yamtarawala further states that, “The moon has peeped out from the sky, beaming with smiles. It’s that time of the night when elders regale the young ones with our ancient tales. We don’t have grey hairs, but we are like elders to these young ones. Folktales are our stories. They are our lives.”

The foregoing allusions and assertions accentuate the rationale for the playwright’s research which has given birth to this play. It therefore foregrounds the imperative of not knowing about our history but also documenting the same for posterity for the benefit of the unborn generation who would be born into a new world bereft of a sense of their cultural heritage and history. It is in light of this that Yamtarawala is a remarkable dramaturgical homage to the Kanem-Borno Empire which many are unaware of some of its history today. Furthermore, the play text provides a theatrical depiction of war scenes through descriptions that offer insight into the nature of life and cultural paraphernalia of the people of the era in focus such as their sense of dressing. It also showcases the tension between the early Muslims and the traditionalists within the textualized communities. For example, the traditional people represented in the text are often described as believing in juju and charms while the Muslim elites are shown as believing in Allah and this assertion can be inferred through Yamtarawala and Galadima’s responses to the mystical powers of each community conquered by them. The communities are said to be protected by powerful charms which Yamtarawala and Galadima often destroy before carrying out their attacks on them. To get to the charms, Yamtarawala pretends to fall in love with the princesses of these communities and even ends up marrying some of them only to destroy their community’s powers by first destroying the charms.

The play text adopts a simple technique in which the actions are grouped into parts and scenes. The overall plot of the text is hinged on the prowess of a narrator’s recollection of the various historical contexts that give rise to each plot. The narrator’s intervention comes either at the beginning, middle, or end of each part providing extra information not contextualized in the dialogue and actions. The language is also accessible to various classes of readers although it is laced with some elements of poetry which enhances the freshness of the dialogue in many instances. The play also portrays a unique anticlimax that strengthens the resolution of the text. For example, the play ends with a rather shocking and unexpected twist; after overcoming the tragedy of losing his father’s throne and going on to establish his kingdom, Yamtarawala is confronted with a greater challenge when his instinct tells him that one of his children is preparing to take over his throne before his death. He therefore sets out to find out which of his sons is plotting to take over his throne by asking his children to boil a stone until it cooks. All the children take turns to cook a stone that refuses to cook except for Marivihyel whose stone mysteriously softens like a cooked potato. This discovery angers Yamtarawala who then plots his son’s death but to his utmost dismay, his son survives the attempted murder on him even though the news of his death is already spread across the kingdom. This portrayal is striking because it is a law of nature that parents build empires for their children to inherit Yamtarawala was not ready to lose his empire to any of his children.

However, regardless of Yamtarawala’s machination, he ends up the way of all mortals as his death is announced in the epilogue of the text. Although he overcame betrayal from his family and won many wars to establish his empire, he could not conquer death. Yamtarawala’s death occasioned by the budding rise of his son Marivirahyel, indicates the end of the old order and the beginning of a new era represented in the foresight and demonstrated cleverness of his son who began to prepare himself for the future by fortifying himself against unforeseen spiritual attacks.

In conclusion, it is important to stress that the beauty of a play is its performance on stage, however, a good play can also be enjoyed as a text as is the case with Yamtarawala. The careful description of its scenes makes it easy to read and enjoy. The play is a quality work that suits the purpose of social awareness creation and education on the importance of knowing one’s history and culture. It is a valuable contribution to the corpus of Nigerian drama and cultural documentation and appropriation. It will greatly inspire young and adult readers alike. The play deserves to be staged and taught to secondary school students, especially in northern Nigeria.

Paul Liam is a poet, critic, author, and communication specialist based in Abuja